|

Well, my mother finally passed over last week.

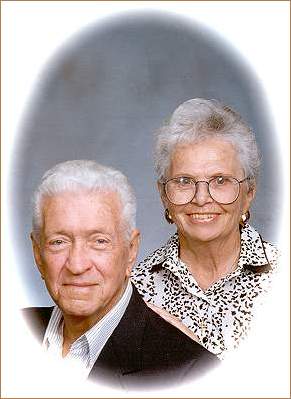

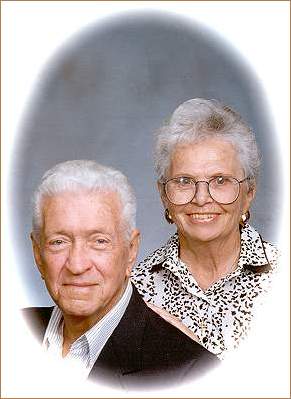

Her last two years were not at all happy ones. She lived in Florida, alone after Dad passed over. Family and church friends made an effort to talk her into moving to Texas, where she'd be near my older brother and his wife (who was Mom's young friend, long before she married my brother). But it was a half-hearted effort; she would never really consider it, and we all knew that.

Moving from Florida would have been the best thing to do, and it wasn't going to happen. She wasn't about to leave the double-wide to which she and Dad had retired. Maybe those first years in the shiny new double-wide were the best of her life: no more back-breaking wage-labor, no more supporting the children, just she and Dad—finally they had it made.

|

|

|

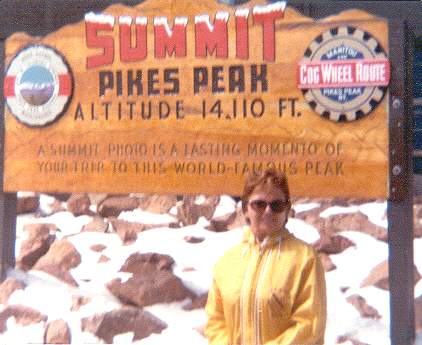

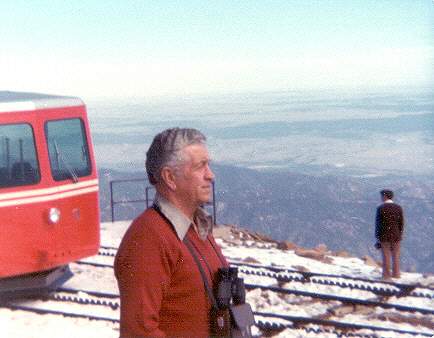

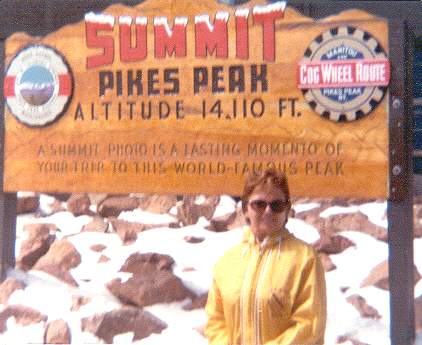

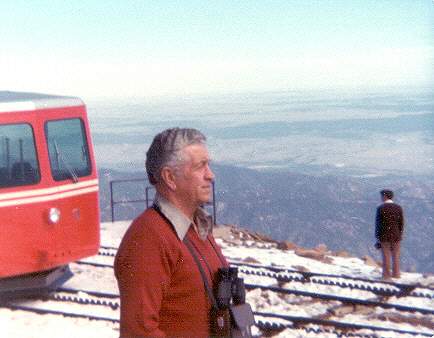

They rode bicycles, they travelled, they played cards with neighbors at the clubhouse. It went like that for a good 15 years, until Dad grew frail. After being healthy all his life, he was sick all the time.

Then he was gone—although his body survived a few years beyond his real departure. His spirit seemed to pass over, two years before his body did, but eventually his body made The Change as well.

|

After Dad was gone, there was just no comforting Mom, or any way to simply "call her and cheer her up," as people used to urge me. She just didn't find anything of substance in this world anymore. For 60 years, the world was comprised entirely of their marriage—and in a secondary way, of the children that sprang out of their marriage. After Dad's departure, Mom always seemed a little confused, as if she couldn't understand why the world was still turning or why day-to-day life continued for billions of people.

I can imagine her utter astonishment that India and Pakistan would consider nuclear war over Kashmir. "What on earth for?" she might have wondered, somewhat bitterly. "Why would they bother? Don't they know your father is gone?"

In her last weeks, Mom decided that eating was optional. After all, why bother? She endured an operation, and there were complications. She needed care, and she was still in Florida; her eldest son lived in Kansas, our middle brother is in Texas, and I'm out here in California. Mom went to stay with a man from her church, who chooses to help people in dire need "as a penance for my past sins." That's where my mother died, in that kind stranger's house in Florida.

The afternoon before she died, the guy left a message on our answering machine. I had never heard from him before. "You should call her and try to cheer her up," he pleaded. "She's not doing well. If she doesn't pull out of this depression, she's not going to make it." I got the message at 10:30pm, Florida time. I decided I'd call the next day, although I didn't want to. I knew I couldn't cheer her up—only Dad could, and all she wanted in this life was to be with him.

Mom believed in the Christian heaven. When she died, she believed, they'd be together again. Well, what could I possibly say when I called? I don't believe in that orthodox Christian heaven, but, for all my study of world religions and philosophies, I've never heard of an afterlife where she'd be more unhappy than she was here, living in this world alone.

So I never did talk with her again. She passed over that night. My wife took the phone calls early in the morning, while I was still in bed asleep. She came into the bedroom, unsmiling, carrying mugs of coffee. I knew what she was going to tell me, and she knew I knew. The news gave me the greatest relief I've ever felt. A very, very sorrowful person was now at peace. Two years of unrelenting grief had ended. I'm not so selfish that I didn't bless her passage.

Of course I didn't fly to Florida for the service. None of the family went. I talked to both my brothers on the phone (and to that curious man in whose house Mom died), but that was all any of us could do. Going to some church in Florida would have been pointless. We all went to work the day Mom died. We wanted to be with the people who make up our worlds, with our friends and our colleagues. What would sitting around at home have accomplished?

But here's what I did:

I packed my drum and took it with me to work. At lunchtime I drove GoGo the WonderCamper to the end of a spit of sand that extends into San Francisco Bay. I hiked out to a bird sanctuary, where a raised wooden platform overlooks the tidal marshes, where Canadian geese forage, and turkey vultures glide, and killdeer shriek and pretend to have broken wings. Up on the platform I played my drum as sweetly as I could, in dark 6/8 time. There I bid my Mom, and finally too my Dad, farewell and thanks. I played for a very long time (much longer than a "lunch hour") until the music gradually faded to a close.

|

When I finally stopped playing after so long, the geese looked up and stared at me, as if wondering if that was it. As my tears cleared away, I realized what I beautiful place I was honored to play in, and I knew that the geese were right to wonder. Passing over is surely part of Life, but Life goes on regardless of who comes and who passes—and never forget, Life is good, even if sometimes living is not.

So I took my drum again and played Bayee, which is a Congolese rhythm whose feeling translates to English as, "Hey ya'll, come to the party!!!" We all come to The Party, and we all leave The Party, but The Party goes on and on forever.

I'm a novice drummer, and I can't sing and drum at the same time yet, so I screwed it up a lot, and I laughed at myself, and a couple of geese honked at me for laughing, and the drum sounded really warm and good.

|

|

Then I hiked back to GoGo the WonderCamper and ate my stone-cold lunch, because a feast always follows a ritual.